The darkness was seeping in on us from every corner. I’ve been down mines before; salt mines, diamond mines and mines for precious stone. I’ve even visited my fairshare of caves, some of my favourites being the include the waitomo caves of New Zealand with the beautiful night sky of the glow worms spread above, or a winter cavern in Germany where ice stalagmites as tall as me rose up from the floor. Yet despite my numerous visits to caverns, caves, mines and underground tunnels, I have never felt the oppression of darkness so strongly as in my visit to a Welsh coal mine.

The Big Pit near Blaenavon, was in operation for a hundred years. Closed in 1980 when the coal seams became depleted, today the pit is kept open to the public for educational purposes. Several miles of mine shafts are maintained for this purpose, but many more have been decommissioned to reduce maintenance costs or closed off due to safety concerns. Yet though the mine is kept in significantly better shape than it would have been before health and safety kicked things up a notch the tunnels are still kept as unpolished as possible, smothered in soot and largely unlit aside from the torches the guides and visitors carry with them. Perhaps it was this, and the light absorbing nature of the soot and the darkness of the unilluminated passages, that made the mine feel so oppressive. Whatever it was that caused it, the darkness about our small group seemed thick enough to reach out and touch. Sensations of suffocating terror seemed just close enough to hurry my step, the feeling as though you might turn a corner and find yourself alone, your one solitary light fighting feebly against all that darkness.

Yet the fact was that we were only visiting the mine, spending less than a few hours within the dark gloomy surroundings. For many this was once a way of life. Before child labour laws came into force in this country a child of no more than eleven or twelve who daily have descended the rickety mineshaft to work away the hours, with nothing but a dim flicking candle to protect them from the gloom.

This mine, like most of the early twentieth century was owned by a wealthy landlord. The workers within it were paid for the weight of coal they managed to extract. As seams were often thin much of the work was done lying down, crawling into a narrow gap, carved by the work of small hand tools. The miner’s young apprentice, often his son, would crawl into the gap behind his father to grab the valuable chunks of coal and deliver them into a container or cart.

On the day we visited the mine was fairly still, only the sound of our footsteps sounding around us, but when it had been in opperation the mine would have rung with the clatter of pick axes, the rumble of carts, and, before engines where brought down the shafts, that the nay of the pit ponies. The air, only refreshed by the breeze blowing distantly in from high above, would have been filled with coal dust, disturbed by the busy workings of the men. On our visit we were expertly guided through the few miles of tunnel kept open for visitors, with no ridk of losing our way, dangerous tunnels safely barred, yet I couldn’t help imagining what it must have been like to find your way back through the maze of tunnels that once existed, back to the light and air away from dead ends and false turns.

Pit ponies were used in British mines from 1750 till 1999. Brought down into the deep dark they were kept in stalls carved out of the stone, young boys having the job of caring for their needs. Their only light would have been that of the lamps, carried by the young charges come to bring them their hay, or the miners taking them to work, the dim light leaving with them once again as the days work was finished. Here they were fed and slept, only leaving the stalls to pull their carts of coal from deep in the tunnel to the mine shaft. Around 50 ponys shared this fate at the Big Pit alone, and some 100,000 ponies were in use at the late nineteenth century. Overtime their sight would fail and their bodies weaken. Most wouldn’t leave the pit alive. Looking at their now empty stalls I couldn’t help but feel a great sadness for these creatures, taken away from the moors above with no understanding of why they must shift in the dirt below. Yet I would never blame the men that took them there. This life was not a choice for the mining communities, it was their only option. For them the use of the ponies saved their already aching backs from breaking, and perhaps made the difference between feeding their children well or barely at all. We often look back at the practices of the past as cruel and barbaric, but the truth is how can we judge when we don’t have to make the same hard choices.

Life in the mines was dangerous. Aside from the long-term damage from breathing in the coal dust, causing a condition nicknamed miner’s lung, the threat of cave ins, flooding and toxic gases were ever-present. Towards the end of the life of British coal mining safety equipment such as gas masks and gas detectors had developed enough to be brought down into the belly of the mine, but long before these were in existence more simple methods of gas detection were used. One of the best known is that of the miner’s canary, brought down in a metal cage to sing away in the dark, sounding the all clear. If the canary fell silent the miners would no the cause and their only choice was to leave the mine as quickly as possible. Yet gases like carbon monoxide and methane could be speedy killers and escape was often mostly luck. The Davy lamp was one of the most innovative and lifesaving pieces of equipment most early mines could possess. Build up of methane had meant that early lamps, with an open flame, could cause deadly explosions. Indeed mines often employed someone to light small patches of methane to get rid of the hazard, a highly dangerous job. The Davy lamp enclosed the flame preventing it from being able to light the gas. However it was also an excellent gas detector. Carbon monoxide, heavier than air, would accumulate close to the ground, meaning men sitting down to lunch could lower themselves into the invisible gas and suffocate. By lowering the lamp towards the floor this gas would be detected if the flame depressed or went out, as not enough oxygen would be present to keep it burning well. Methane by contrast is lighter than air and would accumulate against the ceiling. Burning faster than oxygen the lamp’s flame would grow bigger and brighter if lifted into areas of methane.

Suffocation by gas or death by explosion were bad enough, but the mining itself was often the biggest danger. Particularly in early mining the mapping of the workings were poor and mistakes were not uncommon, such as miners tunnelling into previously flooded passage, unleashing the water’s beyond, or simply digging too deep into unstable rock, causing cave ins. Mining disasters, claimed at times hundreds of lives, were not uncommon. Senghenydd in 1913 was the largest disaster of this kind, with over 400 men and boys lost below ground as a large explosion ripped through the mine works. The tragedy of Aberfan in 1966 is today still remembered, as a large area of mining spoil became loosened during heavy rains and cascaded down onto a primary school below. 144 people were killed, with 116 of these being children. Most deaths however occurred in smaller numbers, and many miners experiencing the terror of being trapped in the dark during cave-ins, desperately hoping rescuers would be able to tunnel them out. Accounts document boys as young as 12 trapped for days, only to have to re-enter the mines once recovered to earn their keep.

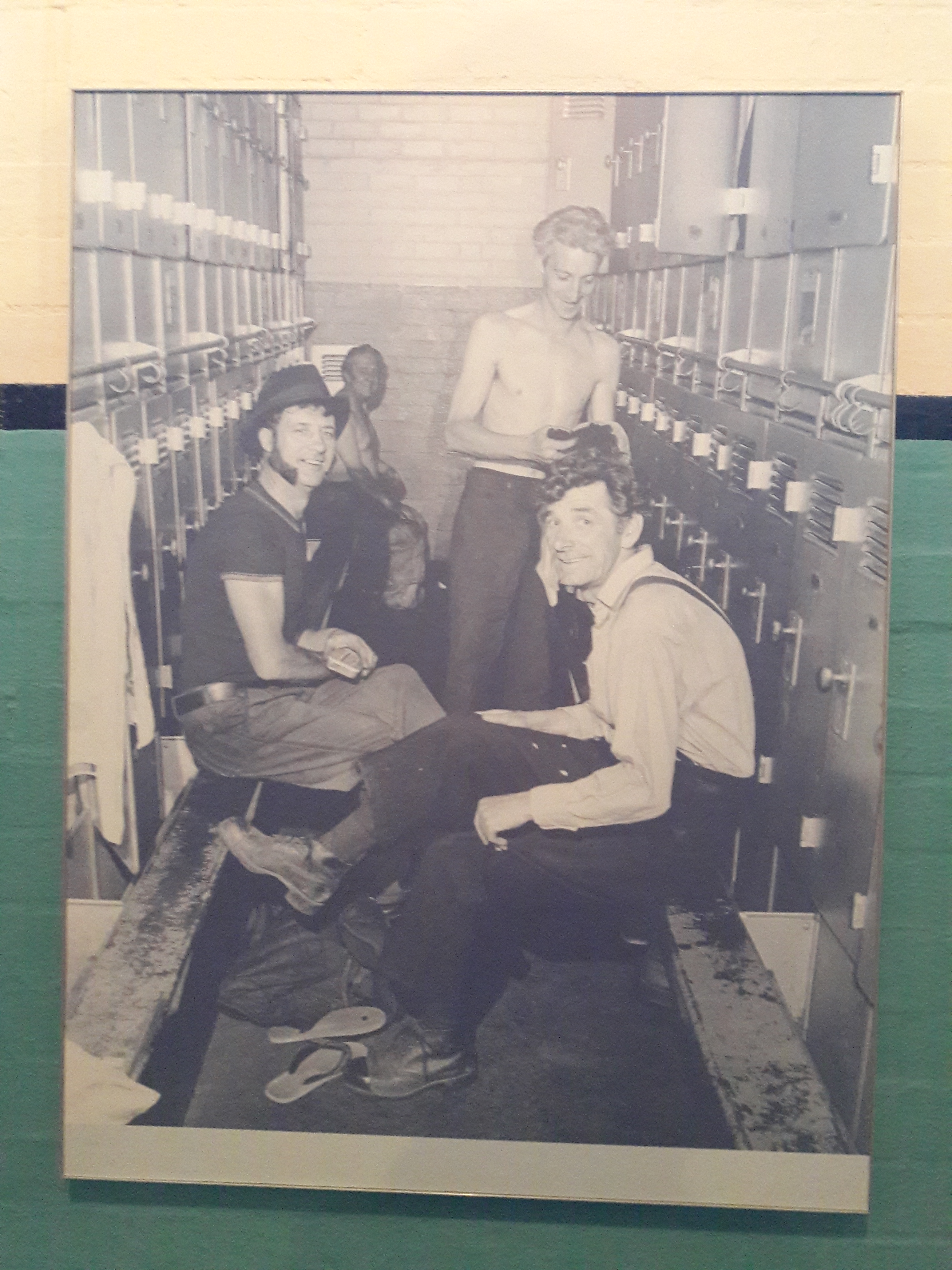

The Big Pit museum has a wealth of knowledge on local mining history, from fossilised trees found within the coal seams, to the ordinary lives of the miners. Many of the miners started their working life by following their dads down into the dark at the age of 12 or 13, and worked the coal until they retired. However some came from far away, immigrants escaping the persecution of the Nazis or Russians, arriving in Wales and making their home in the mines. Some worked their way up, ending life as managers or engineers. But the key thing for many of the rural pit communities was that mining was a way of life, the main source of income for most who lived there. And as the mines began to close throughout the later part of the twentieth century these communities began to suffer.

The miners strike of the 1970s and then the 1980s are still famous today. I have so often heard them spoken of or referred to in films and documentaries that I very nearly felt I understood them, though I never have. Today many people still feel a strong alignment to one side of the other, either angry at the miners for ‘holding the country to ransom’ or angry at the government for bullying the mining communities. It is too vast and complex a subject for me to feel I can do it justice, yet I feel a brief summary is necessary. The miners strike of 1972 seems a fairly simple one, similar to many of the strikes we see today. Pay of the miners had dropped significantly over the proceeding decades to below that of their factory counterparts, which given the physical strain of mining does to my mind seem unreasonable. The strike was brief, only a few months, but caused power cuts and government action to reduce electricity use (the famous three-day week which prohibited people from working longer hours to reduce electricity consumption), which left many people unsympathetic with the miners’ plight. The issue was quickly resolved with a pay rise. The strike of the 1980s, lasting a whole year from March 1984 to March 1985, which brought the force of the unions against the might of Thatcher’s government, is generally a more emotive subject. By this point the large majority of British coal mines had closed, with less than 200 remaining. The cost of mining these remaining areas exceeded the price which could be given for the coal itself, meanings the nationalised mines where working at a significant loss. As an accelerated rare of closures were brought forward the strike flared up. Closures previous to this period had been done with the backing of the National Union of Minerworkers, with support given to retrain the miners, however as Margaret Thatcher pushed forward with more speedy closures and seemingly less support for the miners left behind the union opposed the action. Around 142,000 mine workers were involved in this strike, with whole communities left without employment and little money. The pit workers wanted to keep the mines open, keep their livelihoods and support their communities. The government wanted rid of an industry it saw as costing the taxpayer money and allow market forces to take care of the cost of coal. In the end the government won, significantly reducing the strength of the union, and causing the death of UK coal mining, an industry which had powered the industrial revolution and brought work to many rural backwaters.

The sentiment of the mining community can still be heard loud and clear within the Big Pit. Our guide, an ex-miner himself, as are almost all of the Big Pits guides are (they spend month a year on maintaining the mine itself so perhaps should still be considered miners) spoke warmly of the waste of so much coal left below the ground, and of his wish to re-enter mining proper if possible. And on the final information board of the museum a list of British coal mines and the dates they closed was displayed, like a memorial to the dead. Below this large letters exclaimed ‘We’ll be back!’ Knowing what I do now about the strikes, and having recently spent time reading about the economic benefits of government supported enterprises (a whole different subject but a fascinating alternative to leaving everything to market forces, which cannot truely take into consideration the longterm needs of a nation and its people) I do not think I agree with the wholesale closing of the mines. I certainly don’t agree with how it was done. You need only visit old pit communities to see the lasting effects such sudden and unmitigated closures have caused. Yet finding ourselves where we are now, the pits already closed, coal steadily becoming an old technology ready to be replaced by renewable options, and with climate change an ever fearful apparition stalking amongst us, I also don’t believe in reopening the coal mines. As I stood in that tunnel, the darkness all around, I didn’t get a sense of the future, of things to come, but a sense of the past. My ancestors were miners, one line of our family beginning in Yorkshire and descending to London in later years for work. This may well have been their life. Mining will always be a part of our world, how can it not be when we require gravel for our roads, stone for our buildings and gems for our vanity? But for coal I must admit I feel it better we leave it where it is, a deep sink of carbon, not released to our atmosphere, not adding to our problems. Yet for those communities who still suffer from the lack of this industry certainly more should be done. Perhaps this is where the economic theory of government supported fledging industries should come into practice. Perhaps old mining skills could be put to work by bringing geothermal heat to the surface or money could be invested in supporting the ecosystem services we receive from the hills, forests and bogs of the region? Certainly I think more could be done to honor the places which gave us light and power for so long, at the cost of so many lives. Today I don’t have to contemplate the day when my 12-year-old son has to descend into the darkness and danger of the mine, yet the fact is that I reap the rewards of the generations that did. The Big Pit helped to remind me of this, and its something I wont soon forget.